For young men like Kumar, earning anything upwards of Rs 20,000 is a bonus. Hundreds of people from his village and its vicinity—including passengers on this very train—are always on the move, looking for work in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Surat, and Ludhiana.

Kumar has been living and working in Noida since at least the age of 13. He left his village Maharajganj block of Siwan, western Bihar, after a fellow villager suggested he move to Delhi to work at his tea stall.

“I have been selling chai since then, first in his stall, and then my own tea stall. I make up to Rs 400-500 a day,” he says, as he clambers to the upper berth, already occupied by two men. Selling chai back home isn’t a viable option. “There’s too much crime, and then one needs enough customers who’ll actually buy chai.”

Siwan-bound Jitender Kumar sits in the crowded general compartment of the train from New Delhi to New Jalpaiguri | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Siwan-bound Jitender Kumar sits in the crowded general compartment of the train from New Delhi to New Jalpaiguri | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Kumar estimates that over 300 of the roughly 1,000 residents in his village work in other cities. His friends are making a living in Delhi, Pune, Mumbai, Surat, and Vadodara.

“Most youth from Bihar go out to find jobs. They protest in the capital, they do pradarshans in Delhi demanding vacancies in railways and whatnot, but have zero expectations from the government back home,” he says.

Kumar’s story is a typical one in the Purvanchal belt, famous as the land of Bhojpuri music. It is the country’s labour-supplying corridor in the popular Indian imagination, culture, and memes. Not only is this region a key political bellwether, but its labour migration alters demographics in distant towns and states, routinely triggering cultural, political, and economic anxieties.

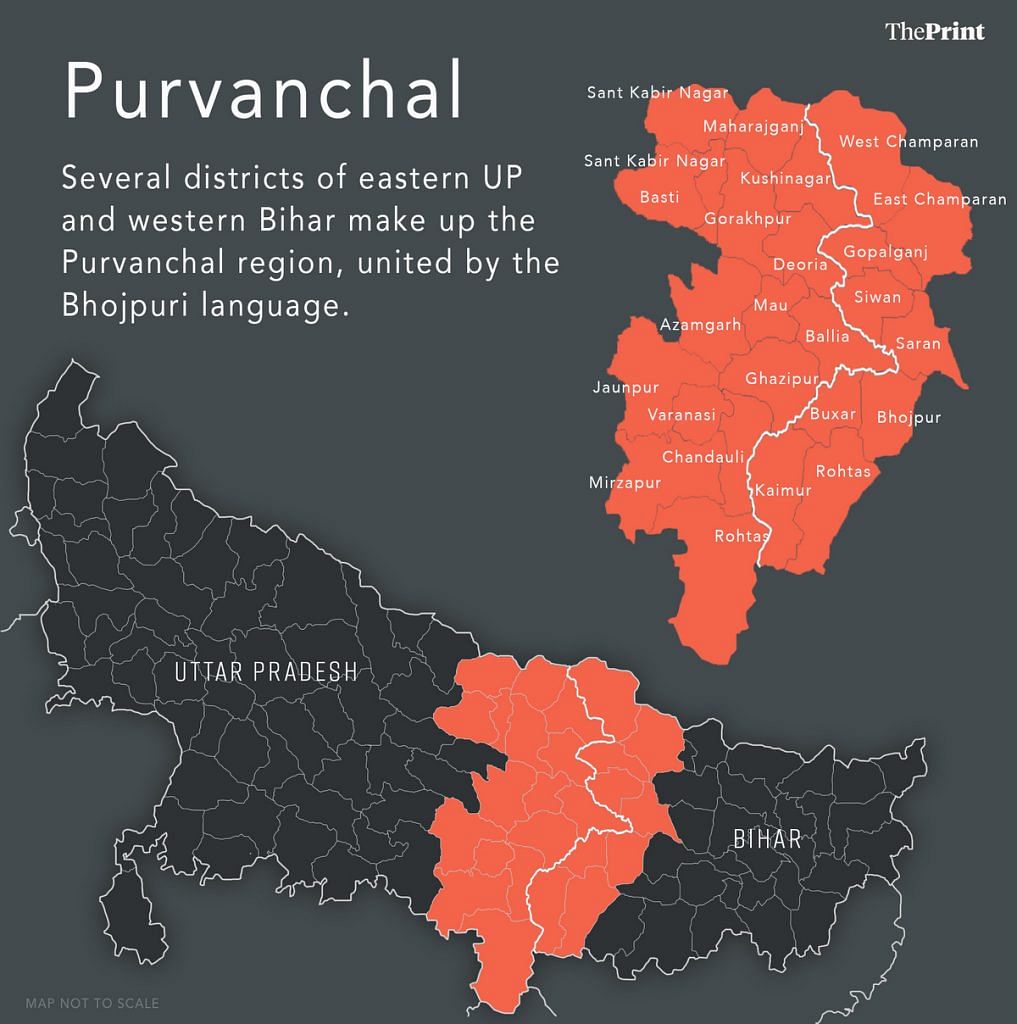

Stretching from eastern Uttar Pradesh to parts of western Bihar, Purvanchal includes towns and districts such as Varanasi, Gorakhpur, Ghazipur, Azamgarh, Ballia, Sonbhadra, Arrah, and Siwan. Bhojpuri is the mother tongue of most people in this 73,000 square kilometre region, and since Independence, there have been repeated political movements and demands from its inhabitants for a separate Purvanchali or Bhojpuri-speaking state.

Graphic: Soham Sen

Graphic: Soham Sen

Several berths on the New Jalpaiguri train are occupied by Purvanchali migrants and their families heading back home for Holi. Everyone has a story to tell—of leaving home, longing, and life elsewhere. Three out of four passengers are men, some in shirt-pants, some in shorts, a few in lungis, and almost all sporting a gamchha. They exude Purvanchali pride, but few want to return home for good.

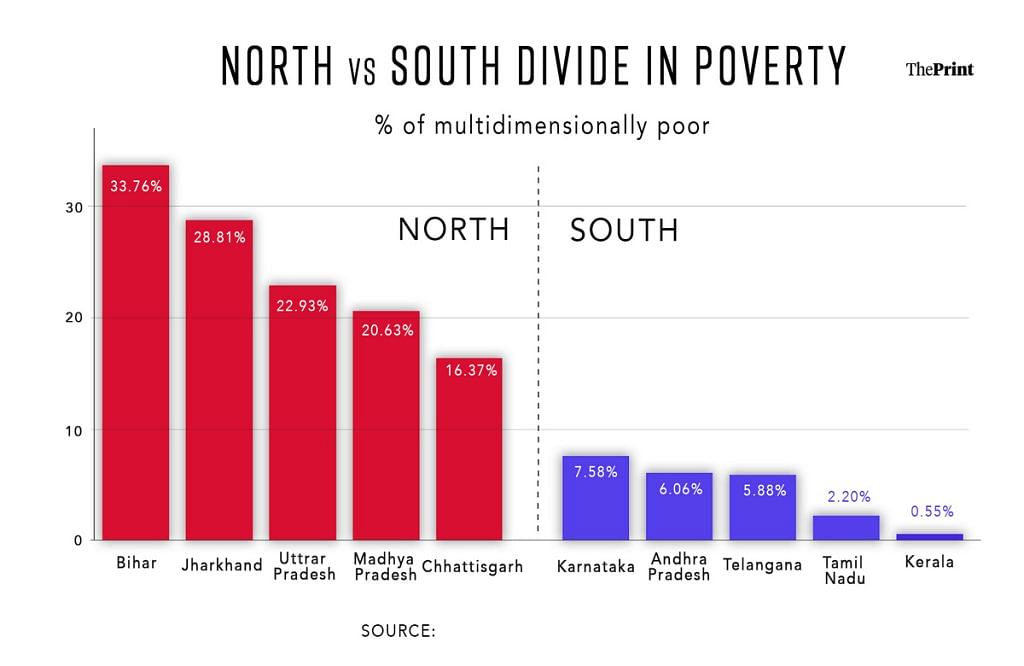

Purvanchal has some of the worst human development indices and socio-economic inequalities in the country. Three UP districts within the region—Shrawasti, Bahraich, and Balrampur—have over 69 per cent of their population classified as “multidimensionally poor”, according to Niti Aayog’s first such index in 2021. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh were ranked the worst and second-worst states, respectively, for the human development indices of education, healthcare, and living standards, per a 2019 State Bank of India report covering 1990 to 2017.

Everybody wants to leave. To date, Bihar doesn’t even have a functional bridge. They all collapse in floods. Good schools or colleges are not even a question. And every politician we’ve had is just catering to their caste

-Vivek Singh from Karmaini Ghazi village in Bihar’s Gopalganj

The cruel irony is that these dismal human development indicators persist despite the region’s central role in the country’s politics.

“Whoever controls Uttar Pradesh, a state more populous than Brazil and poorer than sub-Saharan Africa, has superior odds of capturing the reins of federal administration,” Bloomberg noted.

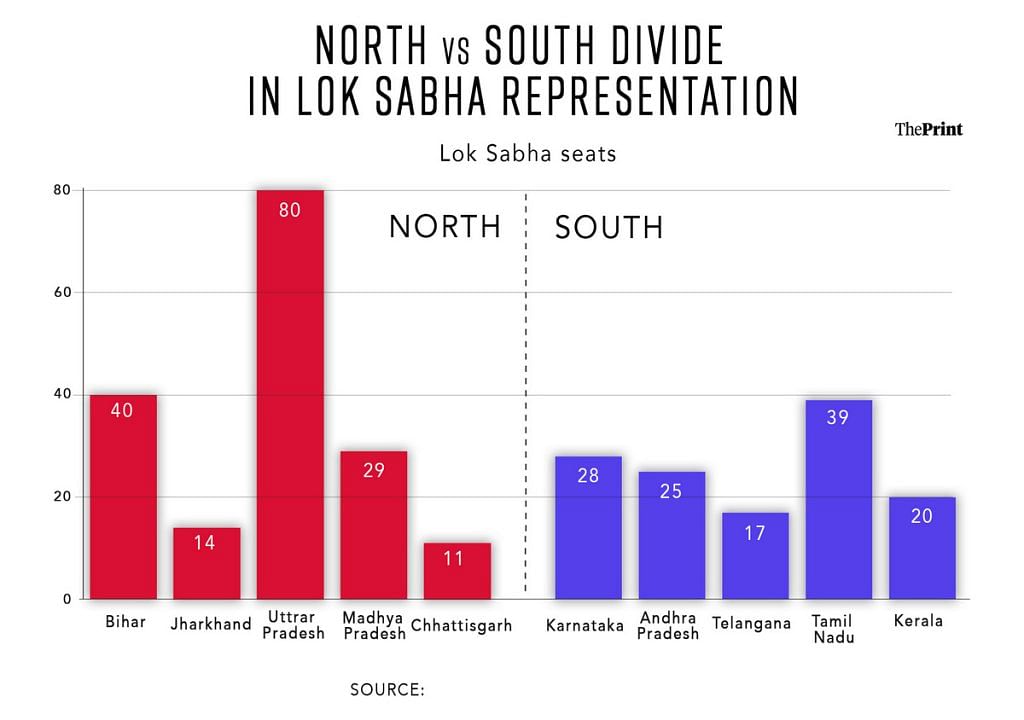

And within UP, it is this Bhojpur region that is catalysing national politics. Its poor economic indicators coupled with its political hustle have triggered a new ‘North vs South’ debate, with southern politicians complaining about central allocations being unfair. It is a new version of the old ‘performing states’ vs ‘non-performing states’ debate.

The hegemony of Punjabi culture over Bollywood plotlines has given way to UP-Bihar stories. It’s a hat tip to the sheer number of eyeballs that the teeming Bhojpur region brings, even if their purchasing power hasn’t caught up yet.

Also Read: Meet India’s ‘dunki influencers’. They teach you how to cross Panama jungle, Mexico border

Pride, politics, penury

Hawkers selling tea, cold drinks, and jhalmuri march up and down the sleeper compartment where an upbeat Vyas Patel carefully removes his shoes and settles himself and his wife into their lower berth.

“I work in Vasant Valley school. Sure, it’s in the sports/physical training (PT) department, but why would I leave this?” asks Patel, 50, who is from the Purvanchal region—Barauli village in western Bihar’s Gopalganj district. “Even if there are now some schools in my village, there’s nothing like Vasant Valley in all of Bihar.”

Yet, many migrant workers carry Purvanchal pride wherever their work takes them across India. They become cultural ambassadors for their traditions, like Chhath puja and Ramleela.

Patel is no different. He is proud of his Bihari and Purvanchali roots and delighted that Bhojpuri’s reach is growing thanks to the internet and migration. He’s also invested in his home state’s future even if he no longer lives here, echoing the long-standing demand for special category status.

Gopalganj-bound Vyas Patel and his wife in the sleeper coach of the train | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Gopalganj-bound Vyas Patel and his wife in the sleeper coach of the train | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

“Bihar deserves a vishesh rajya status. This will help with getting aid from the Centre and dealing with floods and the situation of poverty here,” he says.

Patel’s job as a PT instructor allows him a “comfortably middle-class” lifestyle. He left his village in the early 1990s for a BSc in nursing.

“I did it from Bengaluru, because back then, even our capital Patna had no decent college. My sister is also married to a man working in Jalandhar, all three of my children luckily studied in Delhi,” he says. He even opened a school back in Gopalganj, visiting it a few times each year. But he expressed cynicism at the idea of his own children finding lucrative work in the region.

The crisis in industrial development and jobs adds fuel to the ‘North vs South’ debate. For every rupee that states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala contribute in central taxes, their returns are far less than those given to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. So much so that parties such as the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu and the CPI(M) in Kerala have been raising objections about the erosion of federalism.

Graphic: Soham Sen

Graphic: Soham Sen

“If we pay Re 1 as tax in Tamil Nadu, we get back only 29 paise. But, in North India, in a Hindi-speaking state like Uttar Pradesh, they pay Re 1 as tax and get back Rs 2.73,” Congress’s Karti Chidambaram had thundered while campaigning in Arimalam town for the Sivaganga parliamentary seat in Tamil Nadu.

“What does this mean? You are working hard, you are earning, you are buying things, you pay taxes. And that money is going to North India. Shouldn’t our money come to us?” he added, as his supporters cheered him on.

Some see this as an unfair ‘punishment’ for relative prosperity and population control, including data scientist Nilakantan RS, author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. Uttar Pradesh is too big and corners resources by virtue of its size, and bifurcating it may be the solution, he has argued.

Source: ‘National Multidimensional poverty: A Progress Review -2023’ by NITI Aayog | Graphic: Soham Sen | ThePrint

Source: ‘National Multidimensional poverty: A Progress Review -2023’ by NITI Aayog | Graphic: Soham Sen | ThePrint

But this is easier said than done, given that Purvanchal also boasts of some of the North’s most popular political figures. At least six governors belong to eastern UP, as do several ministers in both the Centre and UP assembly. UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath’s home turf is Gorakhpur, while Varanasi is Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Lok Sabha constituency. A swing region, several of the seats in eastern UP went to the Mayawati-led Bahujan Samaj Party in 2007 and to Akhilesh Yadav and the Samajwadi Party in 2012. But since the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP has increasingly aimed at consolidating its base in Purvanchal.

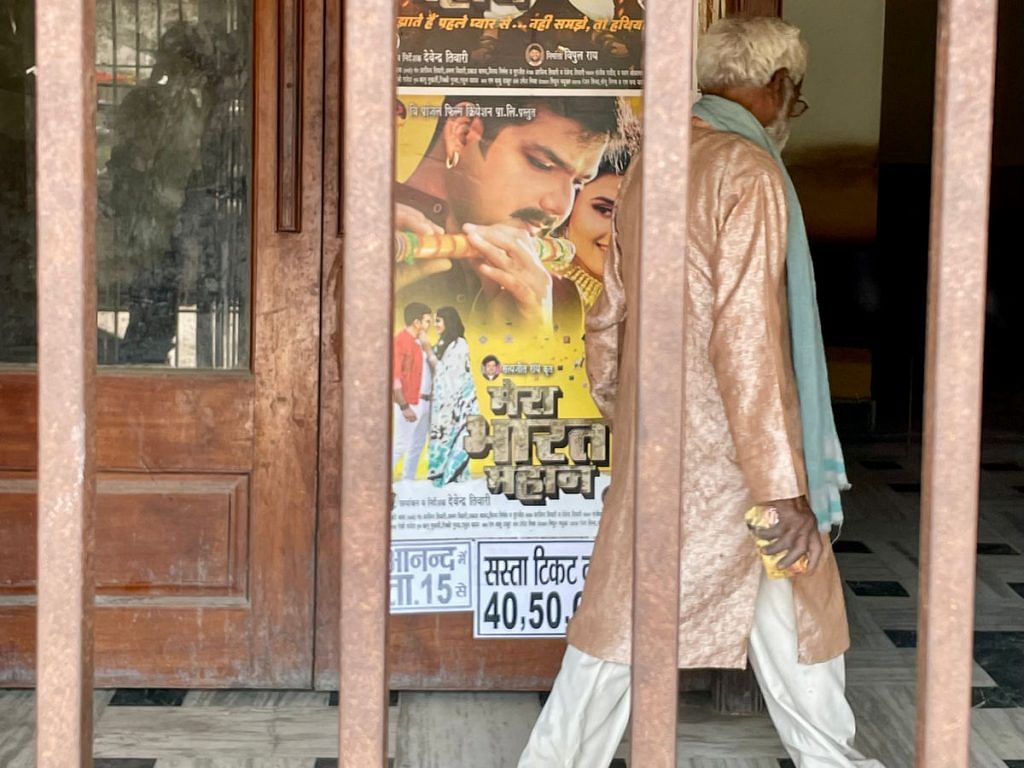

The region’s influence extends beyond electoral politics. Bollywood, OTT series, and the popularity of Bhojpuri cinema and music are slowly transforming the North Indian cultural landscape. Hit movies and OTT series such as Mirzapur, Gangs of Wasseypur, and Saheb Biwi aur Gangster have captured popular interest in this belt, and Bhojpuri stars like Manoj Tiwari, Ravi Kisan, and Pawan Singh have risen to political prominence beyond Purvanchal. The hegemony of Punjabi culture over Bollywood plotlines has given way to UP-Bihar stories. It’s a hat tip to the sheer number of eyeballs that the teeming Bhojpur region brings, even if their purchasing power hasn’t caught up yet.

But the region’s cultural and electoral heft are still far from translating into a socioeconomic turnaround.

The region has a big land bank, but the issue is why would industry and investors come? Massive organised crime surely has decreased, but the local-level gundagardi hasn’t

-Santosh Mehrotra, economist

The train has just crossed Ghaziabad. More migrants from Purvanchal region enter the already heaving bogeys. One of them is Vivek Singh from Karmaini Ghazi village in Bihar’s Gopalganj, who soon enters into a passionate discussion with his co-passengers about his own decision to migrate to Delhi.

“Everybody wants to leave. To date, Bihar doesn’t even have a functional bridge. They all collapse in floods,” he says. :Good schools or colleges are not even a question. And every politician we’ve had is just catering to their caste.”

The two Gorakhpur-bound men facing him nod their heads furiously. “Reservations are part of the problem,” says one.

Singh takes pride in his dominant-caste and landowning Thakur identity. Still, he admits that, reservations or not, there are no good colleges or “worthwhile jobs” back home. With a BTech from Sonipat, he works in construction engineering in Delhi, earning nearly Rs 30,000 each month.

Despite their differences in caste, class, and experiences, migrants like Jitender Kumar, Vyas Patel, Vivek Singh, and others on board this train share two common threads: They all left due to dire unemployment, and they see no industrial growth back home.

With a slew of announcements and projects, including expressways, airports, hospitals and colleges, attempts have been made toward a newfound ‘Purvanchal Vikas Model’.

Caught between rural despair & industrial distress

Around 950 kilometres from where the train originates in Delhi, Bimlesh Paswan, 21, sits under a thatched roof in Nagwa village of UP’s Ballia district, scrolling through Instagram. He’s riveted by reels of his friends and elder brother, who works as a manager at a bank in Varanasi, earning above Rs 30,000. And Paswan, who is in the fourth semester of his BA program at a college in the town, is chomping at the bit for his turn in a big city.

“It was only after seeing my brother that I embarked on my journey for a bank-related job,” he says.

Like most of India’s rural landscape, this sprawl of land where Paswan lives is segregated into caste-siloed ‘tolas’. A Dalit, he lives in a tola on the outskirts of the village. A handful of Brahmins and Thakur own the bulk of the agricultural land even though the village sarpanch is a Dalit. Nearly a dozen men from this tola sit under this shed on a sultry spring afternoon.

“There are no jobs here, haalat bahut battar hai yahaan ke (the conditions of this place are terrible). Since my matric, I’ve seen at least 20 to 25 people from my batch leave for other cities,” says Paswan.

A ‘job advertisement’ of uncertain provenance on the wall of a Patna basti | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

A ‘job advertisement’ of uncertain provenance on the wall of a Patna basti | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Just as he goes back to his phone to check his WhatsApp, Birender Paswan, 52, enters the conversation. Of the nearly 8,000 people in Nagwa, “only 10 per cent”, mostly women and children, remain here, according to him. Flicking through the pages of a local Hindi pamphlet with the Ram Mandir on its cover, Birender says both his sons, 18 and 24, have left Ballia in search of work in Delhi. And he did the same when he was a young man, except he went to Ludhiana. At the time, nearly two decades ago, he earned up to Rs 1,400 per month making sewing machine parts.

Two generations apart, the move-out dreams haven’t changed in this corner of Purvanchal. Young men leave in droves to work as daily-wage labourers, taxi drivers, masons, to find jobs in textile mills and factories. They tap their networks—extended family in Delhi, Ludhiana, parts of Tamil Nadu, and even the Gulf—or go through agents.

It was an uncle in the Middle East who opened 23-year-old Imran Khan’s eyes to a world outside his home in Akhar village, also in Ballia district. Khan’s first trip outside Purvanchal was to Bengaluru, followed by a brief visit to Dubai. That was two years ago. These cities, he says, were “ekdum alag hi duniya jaisa” (a completely different world). In Bengaluru, he worked in an automobile parts factory, making friends and partying. “I now know what eating, drinking, and enjoying get-togethers can look like,” he says.

Bihar is the most flood-prone state in the country, and this is a big source of mass migration. Why can’t the Centre work towards a successful dam and measures for the region. If the Bhakra-Nangal dam could be built, then why not here?

-Samir Kumar Mahaseth, RJD MLA and former state minister

Khan eventually saved enough money to go to Dubai, and it was an experience of a lifetime.

“I loved it so much! If I wanted to start my own business, I’d move to a city like that,” he says. He aspires to earn at least Rs 18-20,000 so he can save enough to move abroad.

While there are no official figures specifically for the Purvanchal region, a 2017 report by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation’s working group on migration showed that 17 districts in India account for at least 25 per cent of the country’s male interstate migration. Ten of these districts were in UP, with most from the Purvanchal region. And more than half of Bihar’s households have been exposed to migration, according to a 2020 study by the Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS).

In UP, the BJP—at the Centre and the state levels—is trying to stem this tide by creating local opportunities. At a 2021 rally in Kushinagar, Modi announced that industrial development in UP was no longer limited to just one or two cities, but also “reaching the districts of Purvanchal”.

The region is crucial to the BJP’s campaign both in assembly and national elections, with Varanasi and Gorakhpur serving as key cities in this belt. With a slew of announcements and projects, including expressways, airports, hospitals and colleges, attempts have been made toward a newfound ‘Purvanchal Vikas Model’.

In 2023, the UP government hosted a global investors summit, with reports suggesting the launch of projects amounting to Rs 10 trillion. Later the same year, Bihar too held a global investor summit, with a reported Rs 50,530 crore worth of MoUs being signed.

Yet, neither this ‘vikas’ nor investments have made a tangible impact on the vast swathes of desperate job-seekers in this land.

Discontent is writ large on the faces of train passengers returning to their home villages— whether it’s Ram Das from UP’s Balrampur, where it’s a struggle to find even “so much as a bread or biscuit factory”, or Siwan’s Jitender Kumar, whose urban ambitions led to selling tea in Noida.

It’s not just the blue-collar workforce migrating, but even those armed with higher education degrees.

Mirage of modernity

At Patna’s City Centre Mall, college students Arshi, 19, and Rayaan, 21, are enjoying the pristine interiors, water fountain, and alluring optics of modernity. But it’s in between scarfing down their pizza that a less-than-rosy reality starts to appear.

“This mall may have a space for young people like us to chill, but this is just an exception, and that too in a capital city like Patna. The reality is there are no investments, and even if any companies do come to invest then it’s in areas like car dealerships or petrol pumps,” says Rayaan, an aspiring model.

Arshi, who is completing her BCom in Patna Women’s College, would rather go to Delhi or Pune for her MBA. It’s the same refrain even among the wealthy.

“There are no good jobs here. There’s no cultural growth,” she says tersely.

Patna’s swanky City Centre Mall with high arched ceilings and decorative water features. It offers a sliver of escapism from the harsh reality of few job opportunities in the state for aspirational young people | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Patna’s swanky City Centre Mall with high arched ceilings and decorative water features. It offers a sliver of escapism from the harsh reality of few job opportunities in the state for aspirational young people | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Inside spaces like this mall, as well as the commercial hubs in other parts of Purvanchal’s bigger cities, it’s easy to forget the desperation—even among more well-off residents like Arshi and Rayaan. It’s not just the blue-collar workforce migrating, but even those armed with higher education degrees.

“States like UP and Bihar have seen big investment summits, sure. There are also much-touted schemes like the ODOP (One District One Product) bandied by the UP government. But the biggest thing needed is labour-intensive manufacturing,” says economist Santosh Mehrotra, a visiting professor at the University of Bath. “Now in Bihar alone, the organised industry has actually seen deindustrialisation.”

Mehrotra, the author of a new report on creating employment in Bihar, says the state only created a concrete industrial policy as late as 2016, which was then tweaked in 2022. “The region has a big land bank, but the issue is why would industry and investors come? Massive organised crime surely has decreased, but the local-level gundagardi hasn’t.”

Data from 2013 shows Purvanchal’s high rate of marginal land ownership, with a big chunk of the region’s agricultural landholdings below 1 hectare, concentrated in the hands of the feudal or dominant castes. Districts like Sonbhadra, Buxar, Siwan, Mirzapur, and Chandauli also saw the rise of Naxalite groups and violent struggles for land in the 1980s and 1990s.

But the lack of manufacturing and industrial growth is a recent phenomenon, claim two RJD MLAs from Bihar—former minister for industries Samir Mahaseth and former labour minister Surendra Ram. Both cite the proliferation of sugar mills and factories until the 1990s.

Former Bihar labour minister and RJD MLA Surendra Ram in his office, as he talks about the state’s unemployment crisis | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Former Bihar labour minister and RJD MLA Surendra Ram in his office, as he talks about the state’s unemployment crisis | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

“The Purvanchal region, and Bihar in general, has seen deindustrialisation in the past two decades. We used to supply coal earlier, and had so many sugar mills and sugarcane factories,” says Mahaseth, blaming the Nitish Kumar-led government for the downturn.

The state was, in fact, a leading producer of sugar in the country, once contributing up to 40 per cent of the total output. But the 1990s saw a rise in input costs and falling prices, causing sugar production units to start shutting down. Even as governments made attempts to revive those factories, they failed to control the deficits and convert the closed-down mills into other viable industries.

Effectiveness is not something that UP and Bihar governments have been famous for, argues Mehrotra.

“FDI tends to flow to states where two prerequisites hold: reasonable levels of governance and quality human capital. And these are precisely the two areas that UP and Bihar have systematically neglected over decades,” he says.

But it’s not just deindustrialisation that’s led to a paucity of jobs. Both eastern UP and Bihar as a whole continue to witness displacements caused by floods.

“Bihar is the most flood-prone state in the country, and this is a big source of mass migration. Why can’t the Centre work towards a successful dam and measures for the region. If the Bhakra-Nangal dam could be built, then why not here?” says Mahaseth.

However, a retired senior IAS officer close to the UP administration disputes the high migration and job-seeking trend. He cites official estimates of 40 lakh migrant workers returning to UP during the Covid-19 pandemic, claiming many stayed back. The expressway and the Ayodhya temple are countering this migration phenomenon, according to him. “They have gotten jobs and work here now,” he adds.

While there’s a perception that migrant men leave behind women-dominated households with more purchasing power due to remittances, research indicates otherwise.

The women and families ‘left behind’

Migration patterns in the region remain uneven and skewed towards men. On the train, too, the few women—wives, children, mothers—are dependents accompanying men.

The stories of migrant work are often told through the perspective of men looking for urban-dwelling jobs, and remittances they send home. But the impact of this out-migration on women and families back home remains vastly underreported. A 2008 study found that 62 per cent of male migrants “leave behind” women and children because they don’t have enough to take their family members along.

More than 4.5 per cent of women in villages and 1.5 per cent in urban areas had husbands living elsewhere, according to the India Human Development Survey 2005. IHDS’s findings also indicated that UP and Bihar accounted for over 23 per cent and 13 per cent of migrant workers across India respectively. About 40-70 per cent of households in both states had at least one member who had migrated for work.

Koi rok-tok nahi hai wahaan (there are no prohibitions in Delhi). People make comments (in Bihar) when I come back. Despite being a daughter-in-law, you are wearing a nightgown instead of a sari, they say.

-Reema Kumari, a migrant worker’s wife from Bihar’s Arrah district

Many women are trapped in a passive ‘waiting wife’ role—whether it’s for WhatsApp video calls, or for their husbands to come home for the holidays. Family decisions are rarely taken without consulting the husbands, sons, and brothers who are away. They live in a state of limbo, punctuated by festivals like Diwali and Holi when most men return home, often with cash and gifts in hand.

In some villages, only a handful of men remain, like Englishpur in the Bhojpuri heartland of Arrah. One of the women living here is 18-year-old Manisha Kumari. After the onset of Covid and the lockdown in April 2020, her father Shyam Bihari Yadav struggled to find work as a driver in Delhi, and the family of six returned home to Arrah.

“Our family lived in Shahdara in Delhi for 15 years. We loved listening to Bhojpuri music there too. I loved playing Khesari Lal Yadav and Nirahua (Dinesh Lal Yadav). If there was any function there then the DJ would play it like they do here,” says Manisha. Yadav now works in Patna, visiting his family once or twice a month.

While there’s a perception that migrant men leave behind women-dominated households with more purchasing power due to remittances, research indicates otherwise. In rural Bihar, households with migrant men are actually more vulnerable to gender-based economic insecurity than those with husbands and fathers present.

“I completed Class 9 from a school back in Shahdara. I would have been in college now if we got to stay on. But here, I just got done with the 10th exams almost 3.5 years later,” says Manisha wistfully.

Despite money sent home by their fathers, brothers, or husbands, women tend to face more difficulties in accessing public goods and utilities like food rations. They also contend with challenges in participating in income-generating activities themselves.

“I completed my BA in 2017, but there was no opportunity for me here. My sister also studied till her BA degree, neither of us can think of a job here. The only working women I know are the ones who go to the main town and operate a grocery store or kirana,” says Pooja Rajbhar, 26, from Akhar village in Ballia. Her two male family members work in Gujarat.

Women like Kumari and Rajbhar do not see any scope in agricultural work, ruling out the possibility of participating in MGNREGA. “It’s very difficult to get job cards, and the benefits of this seem to operate on a caste basis here. There’s too much corruption here,” Rajbhar says.

Freedom isn’t just about economics. Reema Kumari, 23, back in Englishpur to meet her family, is already missing the “manoranjan” (entertainment) and lifestyle available in Delhi. She was one of the few women in the village who moved with her husband to Delhi, where he works at a cable factory. Unlike most village women who wear saris, Reema is clad in a salwar-kameez, no ghunghat in sight.

Reema Kumari chooses to stick with her Delhi style even when she is in Englishpur. She drapes her dupatta over her head for a photograph, but eschews the standard ghunghat | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

Reema Kumari chooses to stick with her Delhi style even when she is in Englishpur. She drapes her dupatta over her head for a photograph, but eschews the standard ghunghat | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

“Koi rok-tok nahi hai wahaan (there are no prohibitions in Delhi),” says Reema. Her husband has two more brothers, both living and working in Delhi, but their wives are still in the village. “People make comments here when I come back. Despite being a daughter-in-law, you are wearing a nightgown instead of a sari, they say. But this is much more comfortable and easier to wear,” she says, swivelling around to flaunt her simple kurta.

The financial health of their husbands and the patriarchal expectations back home ultimately determine whether a woman can accompany her husband to the big city. Reema’s sisters-in-law, for example, live with their in-laws back in Englishpur. But since Reema’s husband earns relatively well and the couple has just one child, he managed to bring Reema along.

The women left behind often yearn for the city because of the promise of more financial autonomy.

“Back in Delhi, my mother used to work as well. She earned money sitting at home assembling phone chargers and packaging them,” says Manisha Kumari. “But there aren’t any such jobs here.”

There’s a tussle brewing between two identities—that of being a working-class migrant and a more entrenched local caste-based identity.

Also Read: In Tamil Nadu’s Tiruppur, Bihari migrants are the new business bosses. Who do they employ?

Bhojpuri songs, caste identity, votes

Musings on migration and separation have found their way in Bhojpuri folk songs for centuries. But now, the theme is a hot favourite among popular Bhojpuri singers, who use it to crank up the vulgarity in their music, from lewd fantasies about ‘claiming another man’s woman’ to portrayals of the submissive ‘domestic’ wife. The genre is now big enough to become a catchment area for politics too—attracting both voters and candidates.

From the BJP to Congress, political parties have been clamouring to get Bhojpuri singers and actors as Lok Sabha election candidates. The BJP has sitting MPs like Ravi Kishan from Gorakhpur and Dinesh Lal Yadav (popularly known as ‘Nirahua’) from Azamgarh. Similarly, BJP’s Manoj Tiwari was elected from North East Delhi, where he will now face off against Congress’ Kanhaiya Kumar. The BJP also recently tried to field Bhojpuri entertainer Pawan Singh from West Bengal’s Asansol, in another attempt to gain Purvanchali migrant workers’ votes, although he is now contesting from Bihar’s Karakat.

Ravi Kishan (right) with CM Yogi Adityanath (left) during the campaign for the 2019 Lok Sabha election | Photo: Praveen Jain | ThePrint

Ravi Kishan (right) with CM Yogi Adityanath (left) during the campaign for the 2019 Lok Sabha election | Photo: Praveen Jain | ThePrint

There’s also a tussle brewing between two identities—that of being a working-class migrant and a more entrenched local caste-based identity. This clash is reflected in Bhojpuri music, where caste-based singers are gaining in influence.

In the recent past, singers have been increasingly vocal about caste, asserting pride in their identity as well as fuelling divisiveness.

Englishpur’s Manisha Kumari and her younger brother Sunny often spend their rationed screen time poring through YouTube videos of singers like Khesari Lal Yadav and Tuntun Yadav.

Tuntun, with over 1.2 million followers on Instagram, is particularly assertive about his caste identity. His handle is ‘Ahiran Tuntun Yadav’.

“We like him because he is from our caste,” Manisha and Sunny say in unison. They concede that a Thakur friend of theirs shows more affinity to a Rajput like Pawan Singh, “because he is from their caste”.

A Pawan Singh or Manoj Tiwari connects (with voters) in cities outside of Purvanchal because once people are outsiders, they see themselves as migrants first

-Brahma Prakash, assistant professor at JNU

–

While a shared identity based on song, language, and musical tradition resonates across Purvanchal, the insider-outsider dynamic of migration also plays a role. When migrant workers return to their villages or towns, caste identity often takes precedence. But in cities like Delhi, their migrant identity foregrounds everything else.

“That’s also why you don’t see any Bhojpuri candidates fielded from Bihar itself. Even candidates like Dinesh Lal Yadav in Azamgarh are being pitched there because of their Yadav caste identity. But a Pawan Singh or Manoj Tiwari connects (with voters) in cities outside of Purvanchal because once people are outsiders, they see themselves as migrants first,” says Brahma Prakash, an assistant professor at JNU’s School of Arts and Aesthetics.

Prakash’s own village of Ganjpar in Patna district has seen many people who migrated to Kolkata, among other cities. He notes many become supporters of the BJP when away, despite being RJD and Lalu Prasad Yadav supporters at home.

The churning within the Bhojpuri industry, however, is not just about voting or political choices, but also a debatable caste assertion. Prakash points to the emergence of a sub-genre of Bhojpuri music where singers from one caste boast about eloping with or “taking” women from another caste.

“On one hand, there’s a caste assertion, especially of OBC groups in these songs. But on the other, they are reproducing sexism… women are seen as property,” he says.

A man enters Anand Mandir Talkies in Varanasi for a screening of the Bhojpuri hit ‘Mera Bharat Mahaan,’ starring BJP MP Ravi Kishan and Pawan Singh. Anand Mandir is among the oldest single-screen cinemas still operating in the region | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

A man enters Anand Mandir Talkies in Varanasi for a screening of the Bhojpuri hit ‘Mera Bharat Mahaan,’ starring BJP MP Ravi Kishan and Pawan Singh. Anand Mandir is among the oldest single-screen cinemas still operating in the region | Photo: Sabah Gurmat | ThePrint

In 2021, a relatively unknown Bhojpuri singer named Pankaj Singh Rajput, also known as ‘Risky Star Pankaj Singh’, sparked a furore with a song titled ‘Kirtiya ke Gata’, aimed at the minor daughter of popular artiste Khesari Lal Yadav. The ditty, which included lyrics such as “Khesariya’s daughter comes into my dreams”, eventually led to Rajput’s arrest. What made it particularly offensive to many was that he is from the Thakur community while Yadav is an OBC.

“This song was not only disrespectful to a young woman, but he was clearly trying to mock our community (caste). And Khesari himself is not like the others (in the industry); he only has one wife. The others keep having affairs, many have two or three secret wives,” claims Manisha Kumari.

Her younger brother Sunny nods in agreement, opening up their mother’s smartphone browser and playing another singer’s “reply” to Rajput’s song. Titled ‘Raat Bhar Lihe Khesari Pankaj Singh Ke Bahin Ke’ (Khesari teased Pankaj Singh’s sister all night) by one Lalu Raj Yadav, it has over 752,000 views on YouTube.

“There are sitting MPs like Ravi Kishan who’re famous for songs with lyrics like ‘lehenga utha de remote se’ (lifting the lehenga with a remote),” says Banaras Hindu University professor and Bhojpuri language scholar Sadanand Shahi. “Pawan Singh’s Asansol candidature announcement caused controversy because of his anti-women songs.”

Shahi, founder of the Bhojpuri Adhyayan Kendra in Varanasi, also points out how Bhojpuri as a language “has always had a number of double-meaning phrases”, but the advent of technology and clicks has heightened sensationalism and voyeurism.

“What goes viral? It’s now either Hindutva pop or erotic/sexist songs. Often the people involved in writing or producing this music are themselves from lower income backgrounds, so the lack of financial viability makes them resort to anything that sells in the market,” Prakash says.

This wasn’t always the case.

Purvanchal’s Bhikhari Thakur, a pioneer of Bhojpuri literature, wrote extensively about migration, women’s struggles in unequal marriages, and the caste system. Films like Nazir Hussain’s Ganga Maiyya Tohe Piyari Chadhaibo (1963), the first Bhojpuri film, tackled social issues such as widow remarriage.

Prakash argues that the Bhojpuri industry suffers from the absence of a conscientious class of public intellectuals, leading to stagnation and deterioration in content.

Despite this, Bhojpuri songs and films have a huge audience. The 2011 census indicates that nearly 5.6 crore Indians identified Bhojpuri as their mother tongue, making it India’s sixth most-spoken language. The movement to make it an official language remains alive, as does the clamour for a separate state of Purvanchal, with regionally powerful political actors like OP Rajbhar leading the fray.

But granting Bhojpuri official language status won’t change realities for migrants like Siwan’s Jitender Kumar. As he rides the train, fleeting glimpses of fields and electric lines blur past the window. It’s like a romantic, hazy image of home, where distance softens harsher truths.

“We want to speak in English and wear nice clothes. No politician (in Bihar) is giving this to us,” says Kumar.

Show Full Article